To Rejoice and to Suffer

What might it mean to rejoice and to suffer—at the same time? Is that even possible?

In a certain way, yes. And one specific example—the story of Horatio and Anna Spafford from some 150 years ago—comes to mind. But first, a consideration of this topic is timely because for four weeks every year before Christmas, many Christians observe Advent, a season of preparation prior to the celebration of the birth of Jesus.

Gaudete Sunday

In the Catholic Church, the third Sunday of Advent (yesterday, Dec. 17, 2023) is called “Gaudete Sunday.” I admit that for too many years of my life, I recognized only a superficial difference between Gaudete Sunday and the other Sundays of Advent: It was the Sunday on which we got to light the pink candle on our Advent wreath (the other three candles are purple).

Even after I learned that gaudete is Latin for “rejoice,” I vaguely thought of the idea of rejoicing on a specific Sunday during Advent as nothing particularly special. After all, wasn’t the whole season of Advent about rejoicing? And as a kid, when December seemed to last for several months, wasn’t making it to the third week simply an indication that the gifts and fun and food of Christmas were almost here? Not exactly.

First, Advent isn’t about partying for four weeks before an even bigger party on Christmas Day. It’s much more about reflection and preparation. Learn more here.

Second, the rejoicing of Gaudete Sunday is not a blissful emotional outburst of glee. Instead, it is a recognition and practice of deep gratitude and peace despite the trials of life. It orients us, giving us hope.

The idea of rejoicing for Christians comes in part from St. Paul’s First Letter to the Thessalonians, in which he wrote (Chapter 5, verses 16-18): “Rejoice always. Pray without ceasing. In all circumstances give thanks, for this is the will of God for you in Christ Jesus.” These verses suggest at least three important points: (1) rejoicing takes constant effort, (2) it’s related to gratitude, and (3) we should do it “in all circumstances.”

What were St. Paul’s circumstances? We know he faced tremendous adversity. As he wrote in his Second Letter to the Corinthians (Chapter 11, verses 25-28):

Three times I was beaten with rods, once I was stoned, three times I was shipwrecked, I passed a night and a day on the deep;

on frequent journeys, in dangers from rivers, dangers from robbers, dangers from my own race, dangers from Gentiles, dangers in the city, dangers in the wilderness, dangers at sea, dangers among false brothers;

in toil and hardship, through many sleepless nights, through hunger and thirst, through frequent fastings, through cold and exposure.

And apart from these things, there is the daily pressure upon me of my anxiety for all the churches.

Tradition also holds that St. Paul was eventually beheaded in Rome. And yet: “Rejoice always.”

It is Well with My Soul

In late November 1873, Anna Spafford and her four daughters boarded the ship Ville du Havre en route to Paris. Her husband, Horatio, stayed home in Chicago on business relating to the Great Chicago Fire, which two years prior had destroyed much of the family’s real estate investment.

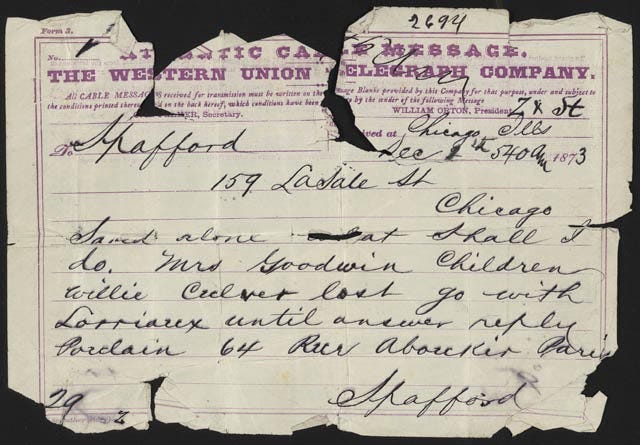

While crossing the Atlantic, the Ville du Havre collided with another ship. Within minutes, the Ville du Havre sank, killing 226 people including all four Spafford children. Back in Chicago, Horatio received the following telegram from Anna: “Saved alone. What shall I do.”

Upon receiving the news, Horatio set sail to meet Anna. During the voyage, the captain of the ship notified Horatio when they were passing the location where the Ville du Havre sank, the final resting place for all of his children. According to this Library of Congress exhibit, Horatio wrote to his wife’s half-sister, Rachel, “On Thursday last we passed over the spot where she went down, in mid-ocean, the waters three miles deep. But I do not think of our dear ones there. They are safe, folded, the dear lambs.”

At that moment, Horatio also began writing the hymn “It is Well with My Soul,” which is still sung today and begins:

When peace like a river, attendeth my way,

When sorrows like sea billows roll;

Whatever my lot, Thou hast taught me to say

It is well, it is well, with my soul.

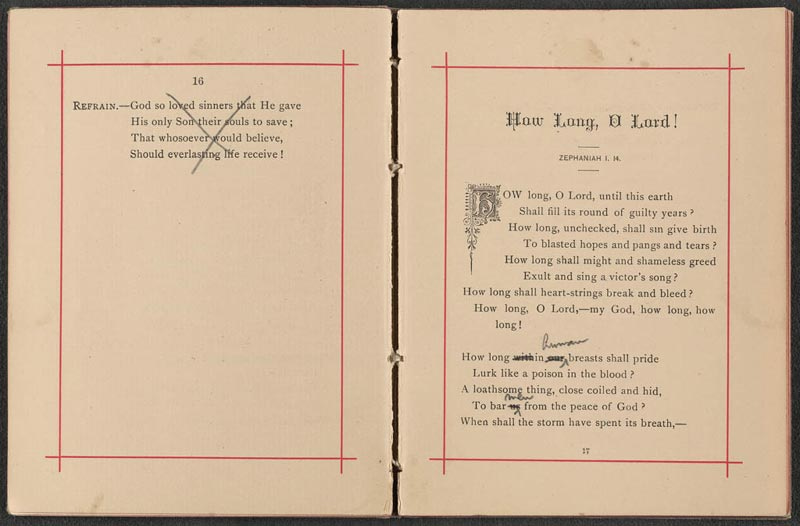

The Spaffords did their best to put their lives back together and had three more children. One of them, their only son, died of scarlet fever. Only two of their seven children survived to adulthood, and Horatio continued on a spiritual journey of sensemaking amid tragedy. Alongside the peaceful, courageous acceptance of “It is Well with My Soul,” Horatio wrote poems such as this one, in which he asks, “How long, O Lord, until this earth shall fill its round of guilty years? How long, unchecked, shall sun give birth to blasted hopes and pangs and tears?”

The American Colony in Jerusalem

In the wake of their family’s multiple tragedies, the Spaffords left their life in Chicago, and with their two surviving children and a small group of other adults, they set off to find purpose and meaning and peace in Jerusalem. Over the years, many others joined their community, which their neighbors dubbed the “American colony,” and they became known for their service of others, particularly during the hardship of World War I.

Perhaps most notably, they began to care for children orphaned by the war. Their efforts grew, blossoming into what continues to this day as the Spafford Children’s Center. Tracing its roots from those fateful moments of tragedy in 1873, the center now cares for hundreds of children and families in East Jerusalem each year.

What might have happened if Horatio and Anna Spafford had succumbed to the bitterness to which one might argue they were certainly entitled?

How might the stories of thousands affected positively by their actions be different?

What happens when we fail to rejoice because life is too hard?

This Christmas, Rejoice Always

I first learned of the Spafford’s story about one month after my son died, when a wonderful friend texted me a link to the extraordinary video below. Christmas that year came only about seven weeks after his death. I remember spending most of Christmas Eve virtually unable to move. There was little rejoicing in an emotional sense.

Yet I did have my faith, my family, and steadfast friends.

And weren’t those reasons enough to rejoice?

I have come to know that one can indeed suffer and rejoice at the same time.

May we all, this Christmas, find peace. May we rejoice, in a deeper and wiser way, alongside our suffering and amid our trials. It can be done, and to survive meaningfully through our hardest times, it seems that it must be done—not in a superficial way, not by lying to ourselves, but in authenticity and truth.

May we all, even when “sorrows like sea billows roll,” have the strength and courage to say and truly believe, “It is well, it is well, with my soul.”