The 9/11 terrorist attacks changed my life in a direct and lasting way. As a senior in college watching the towers collapse on live television that Tuesday morning, I looked around at my fellow midshipmen in the Naval Reserve Officer Training Corps program at Villanova University. The realization began to dawn on all of us that we would be commissioned as officers in the U.S. Navy or U.S. Marine Corps in a vastly different world than the one we thought existed when we woke up that morning.

And we were right.

Many of us ended up serving in some way or another in the Middle East, some aboard ships in the Arabian Gulf, some conducting combat operations in the air, others directly fighting or supporting operations on the ground. I spent a deployment providing maritime security in the North Arabian Gulf during the summer and fall of 2004. Years later, the Navy recalled me to active duty for a year-long deployment to Afghanistan.

Between those deployments and since then, a considerable amount of my work in the military has included some link—direct or indirect—to that day in September 2001. My entire military service as a commissioned Navy officer has been in the post-9/11 world.

And one important reminder of a specific set of events that occurred on 9/11 comes to my mind every time I drive on the Pennsylvania Turnpike, which I’ve probably done dozens of times by now. (It’s generally the fastest way to drive from where I live in Northeast Ohio to Washington, D.C., and Northern Virginia, among other destinations.)

That reminder is a brown sign with white letters indicating the location of the Flight 93 National Memorial. If you’re driving east on the turnpike, the Memorial is located about 50 miles before you get to Breezewood, a few miles north of the town of Shanksville.

I’ve driven past the sign many times but never made the detour to visit the Memorial. But about a month ago, I suggested visiting it to my wife, who agreed that it would be a worthwhile stop as we returned from Washington, D.C., with our children.

I can’t know for sure how much of the story of Flight 93 or the heroism of its passengers stuck in the minds of our kids, but I can say for certain that the Memorial is worth your time for at least two reasons.

First, it’s a reminder of an event that was part of something historic, a day that shaped many aspects of the world to this day.

Second, it’s an example of what heroism can look like. And such examples are important because if nothing else, they show us that courage is a real thing—and it matters.

The Flight 93 National Memorial: An Overview

You can read all about the Flight 93 National Memorial on its website (click here), but here’s an overview.

Let’s start with the context. Flight 93 was one of four airplanes that was hijacked on 9/11. Two of those planes crashed into the World Trade Center towers in New York City; one of them crashed into the Pentagon in Arlington, Va. Flight 93, we think, was headed to crash into either the Capitol Building or White House in Washington, D.C.

On the way toward Washington, however, some of the Flight 93 passengers had learned about what had happened elsewhere in the country. The realized that their hijacked flight was likely headed to a similar fate, that it was also likely to be used as missile to attack another American landmark.

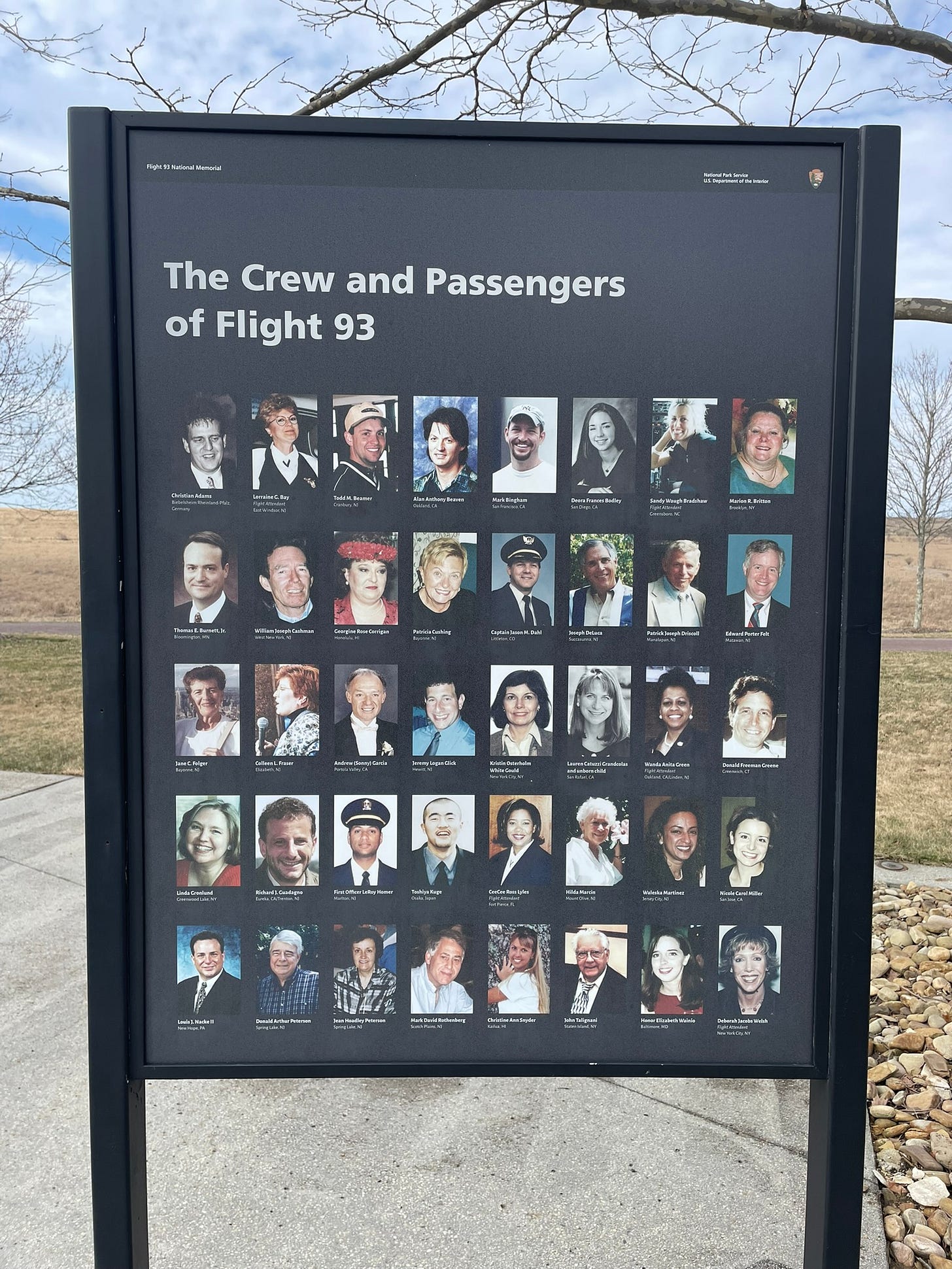

So, a few of them hatched a plan to overpower the four hijackers and take back the plane. In so doing, the plane did still crash, but it crashed in a rural Pennsylvania field instead of in a crowded urban location. All forty passengers aboard died—yet their heroism likely saved many, many more innocent lives.

The Memorial is really three separate features near the crash site: Tower of Voices, a 93-foot-tall tower of wind chimes; the Visitor Center, and Memorial Plaza.

Tower of Voices is the first feature you’ll pass after entering the drive off the main road. Continuing up the drive, you’ll end up in a parking lot at the Visitor Center, which is designed entirely around the actual flight path that Flight 93 took that morning.

That path, looking back toward the parking lot, looks like this:

Beyond the first set of walls is the actual Visitor Center building.

Inside the Visitor Center, one can learn more details about Flight 93 including its passengers and the timeline it followed on the morning of 9/11. One can also listen to the phone calls placed by the passengers to various people on the ground after the hijacking. It is in one of those calls that you can hear passenger Todd Beamer say, “Let’s roll,” which seemed to indicate the start of the attempt to take back the plane.

Back outdoors and following the dark flight path, one ends at this overlook.

Farther down the field from this vantage point is the crash site and Memorial Plaza.

At Memorial Plaza, which you can access either by walking down the hill on a path or by driving to its parking lot, the names of the forty passengers are etched into pillars lining what were the final seconds of Flight 93’s path. In the photo below, you can see the Visitor Center in the distance up the hill.

Beyond Remembering

The Flight 93 National Memorial is important, of course, because it marks the final resting place of forty innocent passengers of what started off as a mundane United Airlines flight from Newark, N.J., to San Francisco.

Yet the Memorial is also important because it serves as an example of ordinary people doing something truly extraordinary. It shows us that courage is real, that it’s possible.

Flight 93 gives us something to point to and say, that’s heroism. But what’s more is that perhaps it awakens the thought of what would I do in a similar circumstance. It primes us to think in slightly different way, perhaps orienting us toward noticing and ideally acting with courage when needed.

So what is courage? First of all, it’s more than just persisting despite fear.[i] The passengers of Flight 93 of course did indeed persist despite their fear, but there’s more to what’s going on here psychologically.

Some years ago, a group of researchers set about the task of really defining courage. They dug through the writings of philosophers including Aquinas and Aristotle; they reviewed the theories and findings of modern social scientists.

Then, they set out on a study of their own in which they asked hundreds of people to categorize different ways to think about courage.

Based upon all of that, they defined courage as “(a) a willful, intentional act, (b) executed after mindful deliberation, (c) involving objective substantial risk to the actor, (d) primarily motivated to bring about a noble good or worthy end, (e) despite, perhaps, the presence of the emotion of fear.”[i]

Now I’m sure the passengers of Flight 93 were terrified. Yet it’s also clear from the evidence that they planned their attack on the hijackers, knew the stakes involved, and realized they they must act to either attempt to land the plane themselves or risk crashing it in a rural area.

The hijacking of Flight 93 occurred at 9:28 a.m. that morning. At 9:57 a.m., the passengers revolted. Six minutes later, Flight 93 crashed. Because it crashed in an empty field, many lives were certainly spared.

There’s another piece of the Flight 93 story, though, one that’s not featured prominently at the Memorial. It’s the story of Marc Sasseville and Heather Penny, two Air National Guard F-16 fighter pilots.

On the morning of 9/11, they were ordered to take off from their base in Maryland. Their task: Intercept Flight 93 and if necessary, take it down with lethal means before it reached the nation’s capital.

Because they reacted so quickly, neither of their jets were armed. They would have to take down Flight 93 in a suicide mission. Sasseville planned to ram the front of the plane; Penny planned to hit the tail section.

Those actions and the additional self-sacrifice proved unnecessary when Fight 93 crashed in fields of Somerset County. Unbeknownst to Todd Beamer and the rest of the heroes aboard who revolted, Sasseville and Penny were two additional souls they saved that day.

May we never forget. And may we reflect upon and consider maybe a bit more often how we ourselves might act if needed in the unforgiving moment, if and when it should come our way.

[i] Matt C. Howard and Kent K. Alipour, “Does the Courage Measure Really Measure Courage? A Theoretical and Empirical Evaluation,” The Journal of Positive Psychology 9, no. 5 (September 3, 2014): 449–59, https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2014.910828.

[ii] Christopher R. Rate et al., “Implicit Theories of Courage,” The Journal of Positive Psychology 2, no. 2 (April 2007): 95, https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760701228755.

Please note: The opinions and views expressed here belong solely to the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Department of Defense (DoD) or its components. Any mention of commercial products or services does not imply DoD endorsement. Additionally, the presence of external hyperlinks does not signify DoD approval of the linked websites or their content, products, or services.