I first learned the details about Sabin Howard and his sculpture, A Soldier’s Journey, about a month ago. That work, how Howard approached it, and how he fundamentally conceptualizes beauty and art have been on my mind ever since. My reaction to all of this has been marinating slowly, and I’m not entirely sure what to make of it all quite yet.

I’m not entirely sure how to write about it either. But I sense that what Howard did and communicates with this particular work of art is really important.

First, here’s some background. Years ago, a special commission selected Howard and architect Joe Weishaar to create a sculpture that would serve as the centerpiece of the World War I Memorial in Washington, D.C.

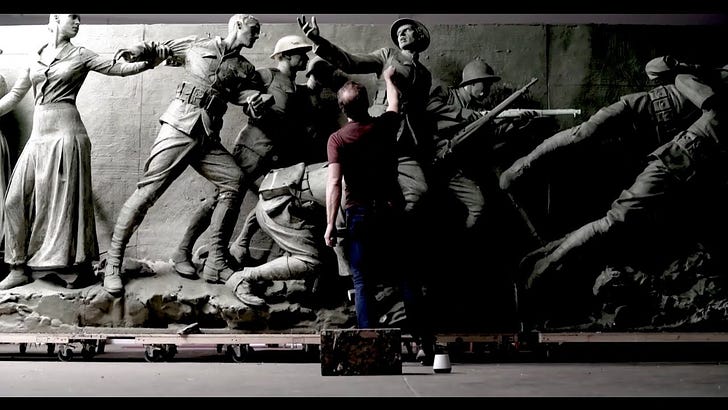

After their selection, Howard and his team worked virtually nonstop for four years to bring to life a 58-foot-wide sculpture depicting 38 figures. The work tells the story, from left to right, of a soldier departing home, joining the war effort, engaging in combat, coping with the mental and physical aftermath, and returning home.

A Soldier’s Journey is set to be formally installed in mid-September 2024 at its permanent location in a 1.76-acre plot at the former Pershing Park on Pennsylvania Avenue NW.

Howard extensively researched and painstakingly created this work of art, employing models wearing authentic clothing from the World War I period of 1914-1918. He used modern-day combat veterans as well to model some of the figures.

The result is nothing short of a masterpiece, capturing the humanity of war at a granular, individual level. It’s in your face and personal, in stark contrast to the cold and distant pillars of the World War II Memorial located about 1,000 yards away as the crow flies. There’s a reason why many refer to Howard as “America’s Michelangelo.”

Here’s a short video in which you can see A Soldier’s Journey and hear Howard explain his approach toward beauty and art in general. In it, he begins by saying,

To create sacred art, you must create something that speaks about the divine nature of how the universe is assembled. Beauty is not just a superficial thing; beauty is about how things are put together.

Beauty shows us the bones of how the universe is assembled.

Sacred Art and the Bones of the Universe

I must confess that Howard’s articulation of art and beauty is one toward which I’m highly sympathetic. I can understand modern “art” to some degree, but it’s just not the same as works like Michelangelo’s frescoes on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel.

I once visited the Andy Warhol museum in Pittsburgh. I walked out feeling debased, not elevated. I felt the urge to take a shower.

So those are my biases.

What’s interesting to me is that Howard clearly views his work including A Soldier’s Journey as sacred art—but there’s nothing inherently religious about it. It’s not overtly Christian like Michelangelo’s Pietà or Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper.

The sacredness of A Soldier’s Journey instead seems to come from its raw, emotional, and accurate depiction of human experience in a poignant trajectory of separation, adventure, duty, heroism, injury, tragedy, and existential grief. Something fundamentally terrible happened to our universe in World War I, and Howard communicates that.

The phenomenology it puts on display, moreover, points toward a bigger truth, something about the nature of existence or being itself. Far from glamorizing war, it illustrates the horror of it all, the toll it takes on individual humans and on us as a collective. It communicates something important about “the bones of the universe.”

That’s the connection it makes with the divine, the sacred.

Sensemaking and the Limits of Social Science

For the better part of two decades now, I’ve been interested in the social science of how we make sense of the uncertainty and ambiguity around us—particularly amid adversity where those disorienting characteristics abound. From the collective body of work on the topic, a number of interesting and potentially useful ideas have emerged.

For example, it seems to be the case that how we make sense of the world stems in part from our own identities and backgrounds. We tend to benefit from engaging in sensemaking with other people; there’s a big part of it that’s social in nature. And how we talk or otherwise communicate about the world around us truly matters because it influences how we think and behave. There’s more, but that’s not the point.

A limitation of social science, I argue, is that it’s highly difficult to measure or describe or explain or predict those aspects of the human experience that defy verbal articulation. In other words, there are parts of the human experience that are difficult if not impossible to talk or write about using language. We are embodied creatures who sense the world around us in ways that are both complicated and complex, and sometimes our attempts to study these matters from the perspective of social science seem to hit an impenetrable wall.

Consider standing on the edge of the Grand Canyon or the first time you stood on a beach looking out upon the ocean. Think about the experience of looking at the Mother of God holding Jesus, her dead son, in the Pietà. Or recall if you can what you feel and think upon walking into a beautiful building, be it St. Peter’s Basilica or the rotunda in the U.S. Capitol.

In a sense, art and beauty matter not because they give us pleasant decorations for our environments. Much more importantly, they give us ways to make sense of our human experience, to gain assurance, perhaps, that there is an order and pattern to it all even when it seems like there isn’t. Truth exists.

Works like A Soldier’s Journey do indeed show us something related to “the bones of how the universe is assembled.” And that matters—not in a superfluous or abstract way—but in a very real and practical way.

These types of art reflect some aspects of truth to us that can and in many ways should influence how we feel, how we think, and how we act.

References and for further reading

More about A Soldier’s Journey and the World War I memorial from the National Park Service

Interview with Sabin Howard on EconTalk:

Reflections on "Why Beauty Matters"

It’s about 100 miles from my home in northeast Ohio to the small town on the Ohio River where my parents live and where I spent the lion’s share of my childhood. I drove there and back recently for a visit, a drive that almost coincided with the peak of the change in autumn foliage colors. Rounding every turn of the highway brought a new arrangement of …