Why We Fight

Sometimes it's clear; sometimes it's not. Yet the question is always worth asking.

“What if we had lost?” my friend asked.

We had just finished a tour of The National WWII Museum in New Orleans, La. As our eyes adjusted to the sunlight outside, we walked quietly down the sidewalk, subdued in the wake of his question and our experience in the museum.

I thought about what a post-1945 world might have looked like had it been dominated by the Axis powers including the German Reich and the Empire of Japan. I considered what kind of world it would be if those who perpetrated the horrors of Auschwitz and beyond or allied with those who did had won the war.

I thought about a world in which that particularly egregious type of horror persisted, one in which such types of power went unchecked.

War is complicated, with many variables influencing motivations and outcomes. War is complex, with many tough-to-decipher implications and meanings. It’s a crucible to be avoided when possible.

As William T. Sherman, a general in the Union Army during the American Civil War, once wrote, “It is only those who have neither fired a shot nor heard the shrieks and groans of the wounded who cry aloud for blood, more vengeance, more desolation. War is hell.”

With all the caveats in mind about history being written by the victors and in full knowledge that innocence is hard to find in any conflict, it does seem to me that World War II stands apart from other conflicts throughout the past century or so. It stands apart for its magnitude, but it also stands apart in terms of its clarity.

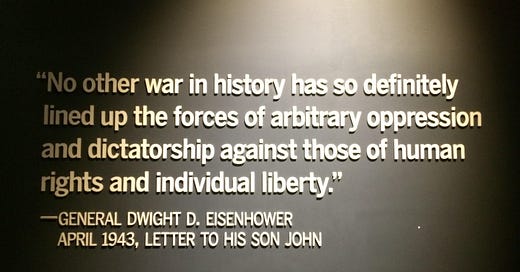

World War II seems at least in my mind to be one of those times in human history in which why we fight was relatively easy to articulate from the perspective of the Allies. U.S. General Dwight D. Eisenhower stated it this way in words that are now affixed to a wall in the WWII Museum:

Given that I’ve been a U.S. Navy officer for more than two decades, I’m somewhat embarrassed to admit that it was within the past few months that I finished watching Band of Brothers, a 2001 American war drama miniseries that tells the true story of “Easy” Company, part of the U.S. Army’s 101st Airborne Division.

The story follows Easy Company from its early days of training in Georgia to the invasion at Normandy, followed by intense fighting across France and other parts of Europe.

In the penultimate episode of Band of Brothers, Easy Company enters Nazi Germany. While patrolling outside a small town, they stumble upon a concentration camp. They look upon the emaciated prisoners in horror and begin the process of assisting and freeing them.

The commanding general in charge of the 101st orders the local German civilians to go to the camp to bury the dead. They do so, sorting through piles of bodies. They encounter face-to-face that about which they claimed ignorance.

The title of that episode of the show is simply, “Why We Fight.”

Why do I fight? Why do you fight?

Of all the episodes in Band of Brothers, “Why We Fight” sticks the most in my memory. In a way, it’s the crescendo of the plot, helping to give some purpose and meaning to the violence and death that preceded it. It didn’t bring back the lives of those in Easy Company who died, of course, but it at least provided some context that makes their deaths seem less in vain.

Yet beyond big stories about war, it made me think at a different level about why I—and we—fight everyday. Why we fight in this context isn’t about interpersonal conflict. It’s about why we do anything that’s hard, why we persist against the odds.

Why do we get up in the morning?

Why do we work?

Why do we try to learn?

Why do we take care of each other and ourselves?

Why do we get up when life knocks us down?

All of these things are hard, yet many of us try to do them anyway.

Sometimes we do these things because we have goals, which motivate us toward achievement. Others of us might also have aspects of our personality that drive us onward, innate ways in which we’re wired that keep us moving.

One psychological factor that seems to play a role in this is the idea of hardiness, a characteristic that helps us withstand adversity. It’s something that varies to some degree between people—some of us have more or less of it—and some of it likely comes from our hard-wired psychological patterns and some of it likely comes from what we learn and develop.

Hardiness has three components: commitment, control, and challenge.

Commitment comprises our sense of purpose and meaning; it’s central to “why we fight.” The Jewish psychiatrist and Holocaust survivor Viktor Frankl often referenced Friedrich Nietzsche’s words, “He who has a why to live for can bear almost any how.” Knowing why you fight matters.

Control has to do with our sense of agency. Retaining a sense of choice within adversity, even if it’s only about having a choice regarding your reaction to the stress around you, helps us move forward.

Challenge involves our approach and mindset regarding hardship in general. To the degree that we can view hardship as a challenge more than as a threat, we can keep our sense of motivation and will to persist.

The Question is Ours to Answer

Sometimes why we fight—our mission and purpose, that from which we derive meaning—is clear. You and I likely aren’t engaged in directly fighting Nazis, but we likely do have some endeavors for which it’s obvious why we persist.

Sometimes it’s not clear. I heard somewhere, for example, that keeping a tidy house while you have children can often feel like brushing your teeth with a mouthful of Oreos.

Yet there seems to be value in focusing on the question—our “why,” our mission, our purpose, that from which we derive meaning. Too many times, perhaps, we get focused in on how we are going to make it through some ordeal or persist in the mundane challenges of everyday life.

That’s understandable and useful in its own right, but it’s not particularly motivational. For motivation and a renewed sense of persistence, it’s likely that we’ll benefit from less of a focus on how we fight and more of a focus on why we fight.

If nothing else, persisting in our struggles provides an example to others—our children, our friends, our acquaintances, and even complete strangers who happen to notice—that it’s possible. And sometimes that’s enough of a “why” to keep on fighting.

References and for Further Reading

Kevin J. Eschleman, Nathan A. Bowling, and Gene M. Alarcon, “A Meta-Analytic Examination of Hardiness,” International Journal of Stress Management 17, no. 4 (November 2010): 277–307, https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020476.