"I don't feel good. But I think I feel better."

Reflections on The Hole, a book by Lindsay Bonilla

“Don’t read this book right now,” my wife said, a few tears glistening in the corners of her eyes. “Wait until after your meeting.”

She was sitting in our kitchen with her almost lifelong friend, Lindsay Bonilla, whom I’ve also known for almost 25 years. Lindsay went to high school with my wife, who coincidentally shares the same first name (some of their mutual friends call them “Lindsay squared”).

Over the years, Lindsay Bonilla has written a number of children’s books. We knew this one was forthcoming, and we knew it was about grief and was based loosely upon her reflections on our family’s tragedy in 2020.

I heeded my wife’s warning and didn’t read the book right away. I quickly waved instead as I passed through the kitchen and headed to my home office to finish a few calls and online meetings.

The next day, I mustered up the courage to read the book. I’m glad I waited.

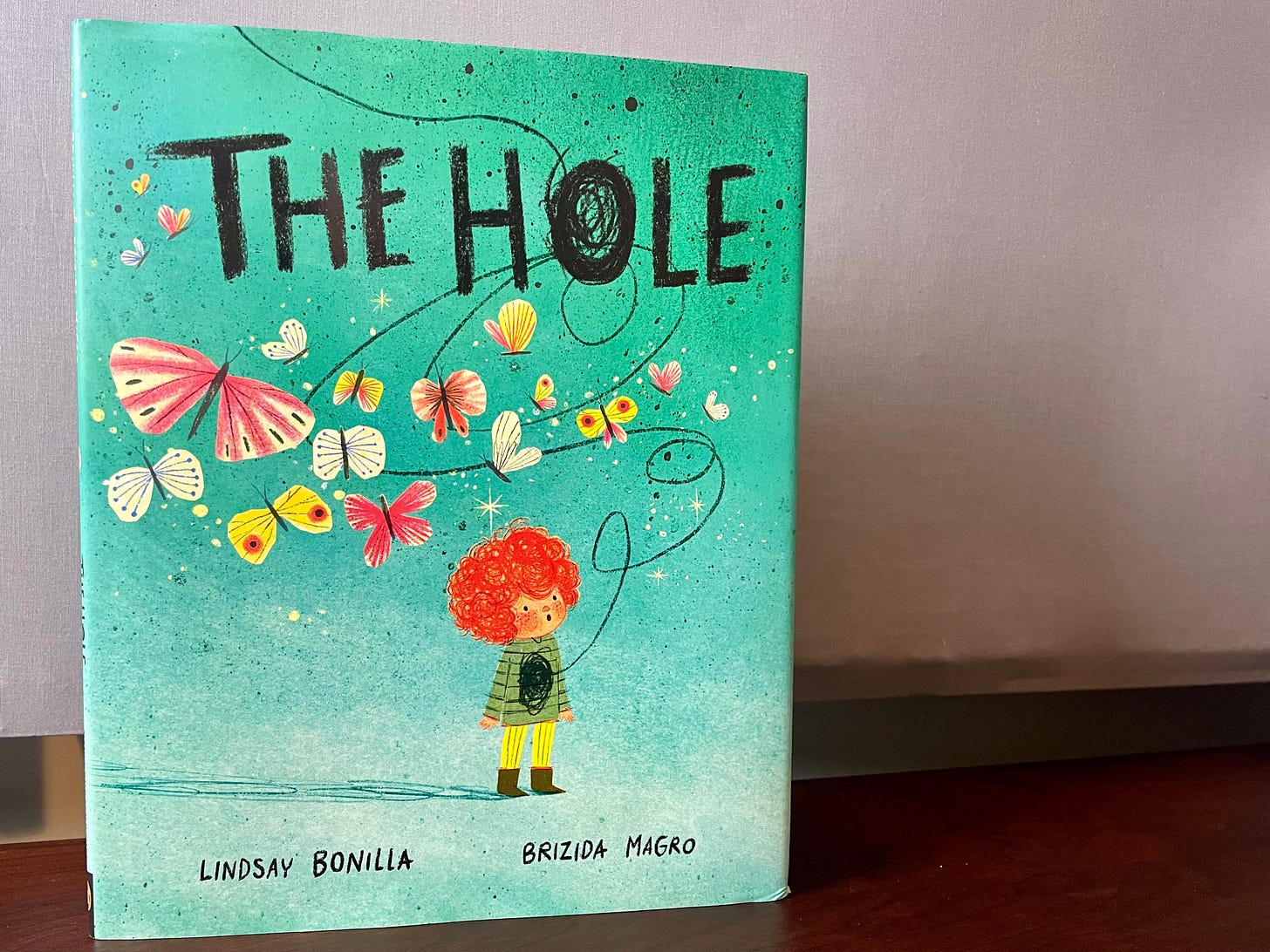

It’s called The Hole.

Written by Lindsay Bonilla and beautifully illustrated by Brizida Magro, The Hole tells the story of a little boy whose brother has died. Instead of seeing him in all the familiar places, he only sees a hole. There’s one on the bottom bunk of his bed. There’s another one where he used to sit.

The boy carries a hole with him, too. Some people notice it; some don’t. A few tell the boy about their own holes: “My grandma.” “My dad.”

Eventually, the boy confronts his hole. He stares at it, joined by his friend. At the bottom, he also confronts the reality of his emotions and the loss.

And then,

“I sit in silence for what seems like a long time. I don’t feel good. But I think I feel better.”

With his friend, the boy finds ways to remember his brother, to fill the hole with memories of him. He learns that although he hates the absence of his brother, he doesn’t hate the hole anymore.

It’s a children’s book, but it’s so much more.

During the past few years, I’ve increasingly realized how the formulaic nature of academic prose fails to describe fully the human experience. This is even true within the social sciences, academic disciplines like psychology, communication studies, and sociology—disciplines that are in fact focused upon understanding, explaining, and predicting human experiences.

That’s one reason why we need the arts—including literature, music, theater, painting, and sculpture—to help us reveal the mysteries of human existence and to communicate certain truths about it. It’s why Sabin Howard’s masterpiece sculpture, A Soldier’s Journey, is an important cultural artifact that expands our thinking about war. It’s why Michelangelo’s Pietà communicates something that just seems really important about life, death, loss, and the sacred.

The Hole is certainly a children’s book. It’s written simply, breaking down complicated emotions into manageable concepts. It’s full of illustrations to guide the imagination. If you were to look for it in a bookstore, you’d find it in the children’s section.

Yet perhaps like many high-quality works of art, The Hole shows us something beautiful. And by that I mean beauty in the way that A Soldier’s Journey sculptor Sabin Howard talks about it, as that which “shows us the bones of how the universe is assembled.”

What “bones” do The Hole reveal? It shows us that grief is palpable, that the death of a loved one actually feels like a physical piece of you is missing. It reveals the necessity of facing our adversity head-on, and the benefit of doing so with a friend.

The Hole helps us see that existence in a broken world is possible, and that persisting in life can coincide with the memories of those we’ve lost. In a way, too—and perhaps at the highest level—The Hole subtlety reminds us that grief is the price we pay for love.

Myriad children and adults everywhere will likely find a piece of their own stories in this book. It’s an important work, as it’s one that helps us articulate a big part of what it means to be human.

To learn more about The Hole including how to order it, click here. Thanks, Lindsay Bonilla, for writing it.